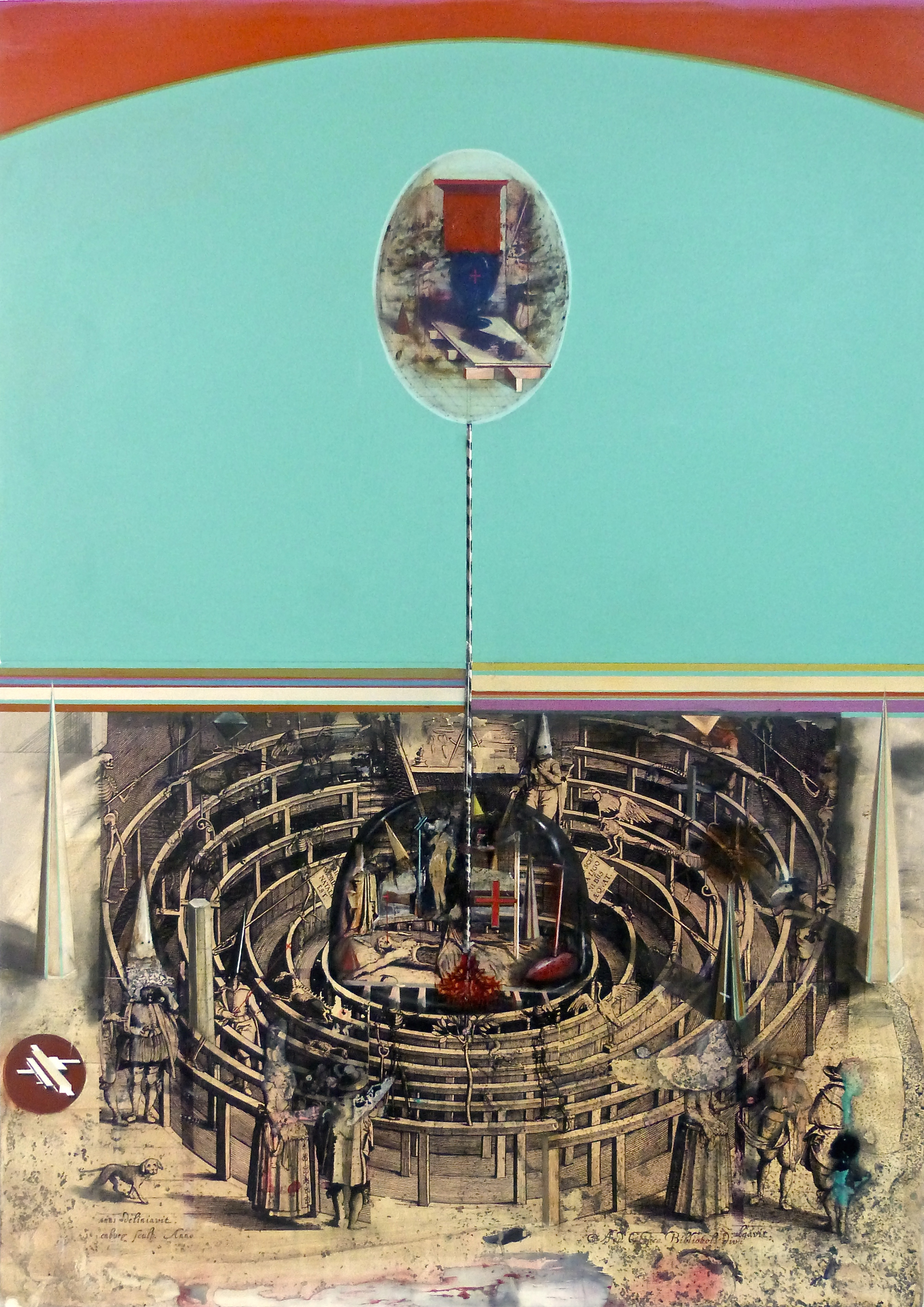

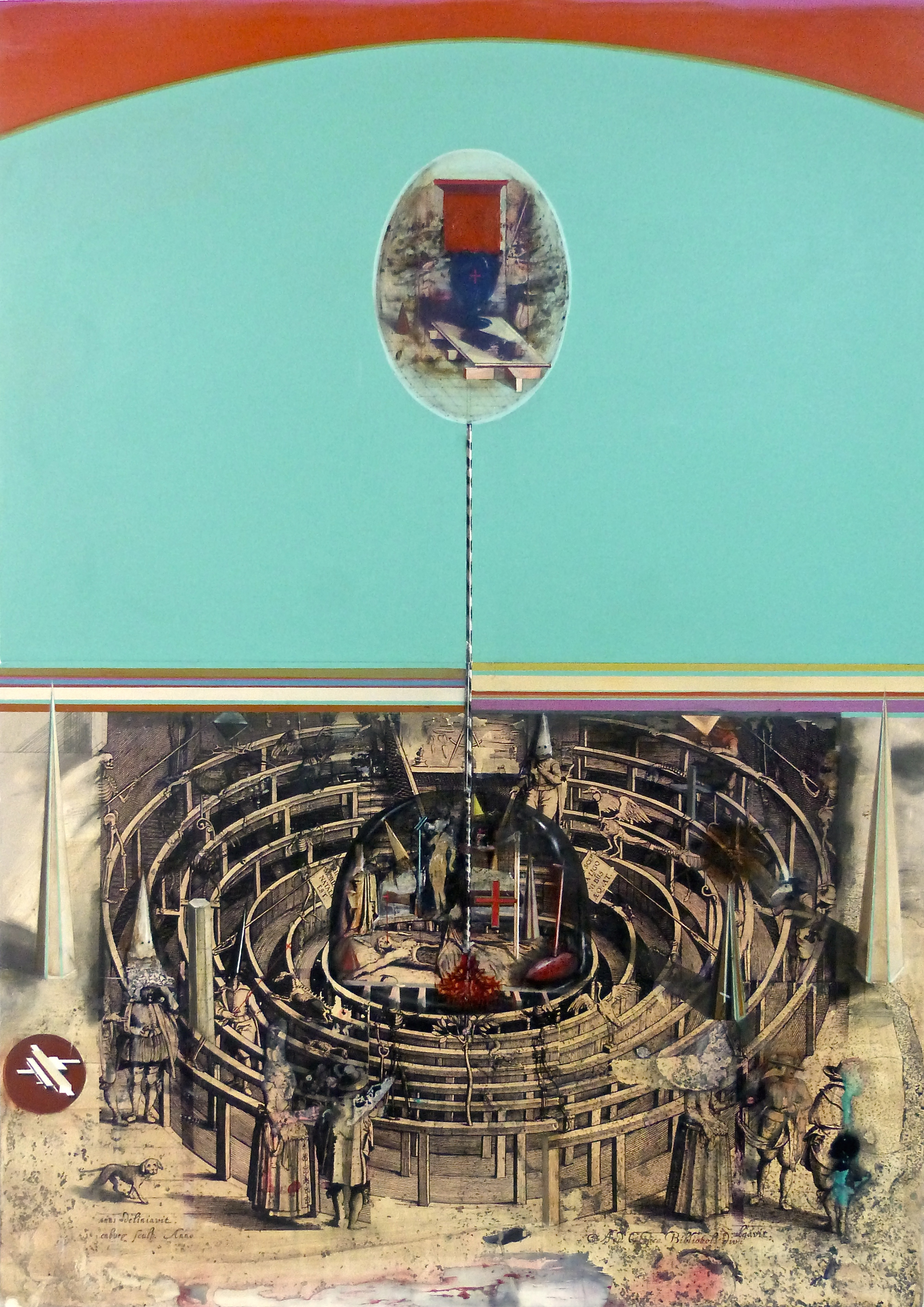

Amphitheatrum mixed media on wood panel 140x100cm

Amphitheatrum is an emblem of disorder; a microcosm of chaos; a mystical demi-monde; une petite apocalypse.

It is set within a 17th century engraving of the Anatomy Theatre at Leiden. Petrus Paauw, Professor of Anatomy, speculated about an anatomical theatre, inspired by classical examples such as the Colosseum, where each member of the audience had an unrestricted view of the arena. He travelled to Padua in Italy and after his studies there, he lobbied in Leiden for a permanent theatre. His wish was fulfilled in 1594, several months before the theatre at the University of Padua opened.

Leiden and Padua became the first universities in Europe to offer public anatomy lessons. The demonstrations took place every year in the winter – in the summer the corpses would start to decompose too quickly. The public dissections were a high point in the academic year; lectures would be halted and the bells would ring.

But by the end of the 18th century the theatre had become little more than a fairground attraction. The once illustrious institution became the object of contention: an increasing number of people, both within and outside the university, condemned the public dissection of corpses as vulgar spectacle. In 1821 the anatomical theatre was dismantled.

In Amphiteatrum, the image of the decaying anatomy theatre is overlaid with a kind of ‘Inverso Mundus’; a medieval genre depicting the world-upside-down or feast of fools. It is a world in chaos with the natural order reversed, where death itself itself represented by the mask of the plague doctor and the apocalypse has become a form of entertainment. A cast of eccentric creatures and characters circle the anarchic scene taking place in the glass dome at the centre of the theatre. This in turn, is linked to the upper part of the work by a column leading to an oval vignette containing a poisoned chalice, set against a landscape of skulls.

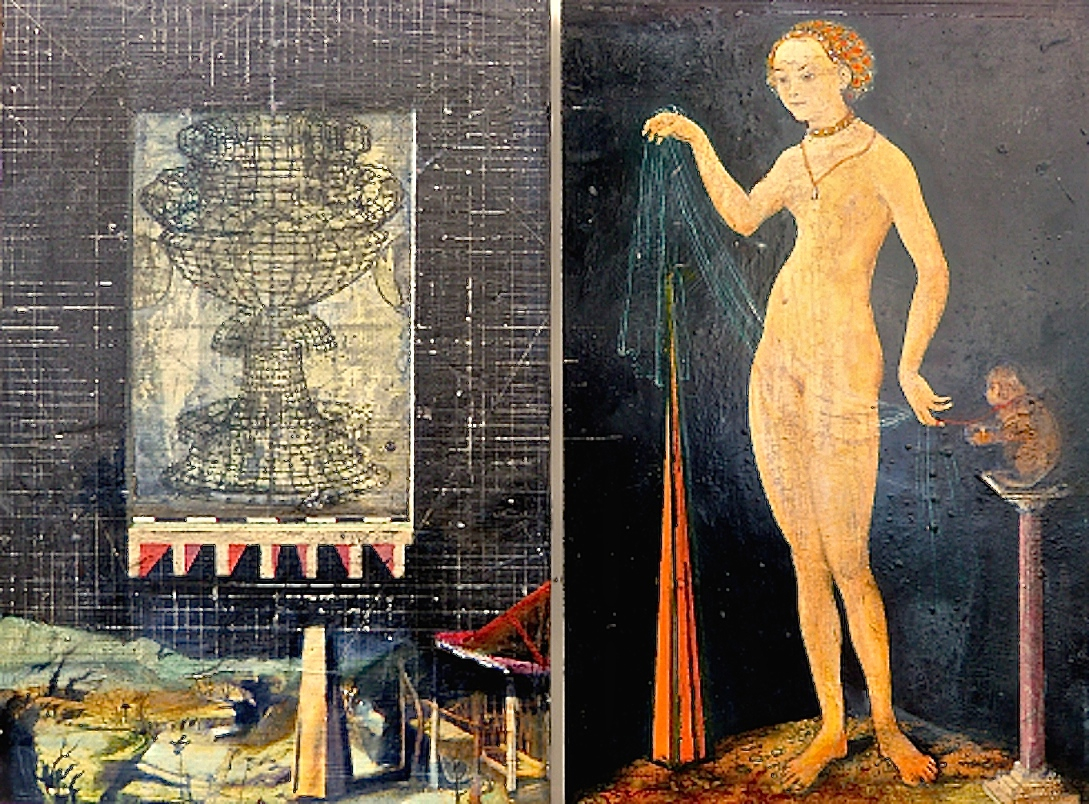

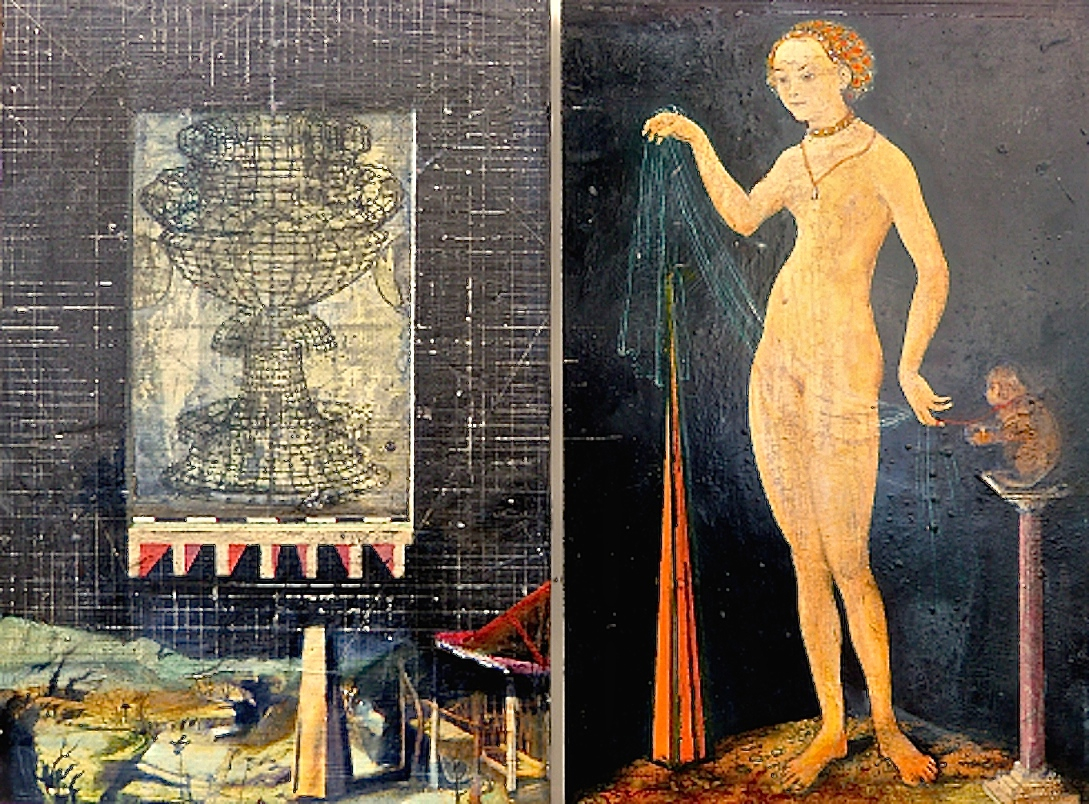

Pithos mixed media dyptch 2x wood panels each 30x20cm

The work Pithos is a dyptch, painted on two gessoed wooden panels. The subject is the Greek goddess Pandora, on the right hand panel, with the infamous vessel, on the left. The vessel is often mistakenly called ‘Pandora’s Box’, which is a mistranslation of the original Greek word was ‘pithos’, which is a large jar. It was used for the storage of wine, oil, grain or other provisions, or, ritually, as a container for a body for burial.

The mistranslation of pithos is usually attributed to the 16th century humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam who translated Hesiod’s tale of Pandora into Latin. Erasmus rendered pithos as the Greek pyxis, meaning ‘box’. The phrase ‘Pandora’s box’ has endured ever since.

According to the myth, Pandora opened the jar (pithos), releasing all the evils of humanity, leaving only Hope inside once she had closed it again. The Pandora myth is a kind of theodicy, addressing the question of why there is evil in the world.

Pandora, here, is based on the figure of Venus as painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder, in 1532. The naked figure is bathed in light, and the background behind her sinks into a cosmic and inexplicable darkness. Today we are familiar with such effects from photographs, film and stage sets. In Cranach’s time it would have been read as a surreal unworldly image which could not have been associated with an earthly being. A depiction of Venus as enigmatic, seductive and intimate as this would most likely have been made for a private cabinet of art and curiosities.

Here also, Pandora has a monkey. In ‘vanitas’ still-life painting the monkey is usually representative of chaos.

In the left-hand panel, the dangerous pithos is depicted as a chalice, that most holy of forms. Legends turn on the talismanic properties of the chalice and the secrets it can bestow. It is the medieval form of the collision between Christian doctrine and magic.

Here, Paulo Uccello’s c.1430 seminal analysis of the chalice is a renaissance exercise in the coding of three dimensional form which prefigures the geometries of Reid, Reimann and Einstein, not to mention the spatial nets which underpin computer graphics.

This pithos/chalice floats against a black void and geometrical grid, and above a mystical landscape. It represents a geometry of the mind which can transmute without warning from the parameters of mathematics to the edges of myth and religious symbolism, and back again.